“In Japan you must be good!” These words, spoken by a cowed villager, mark Englishman John Blackthorne’s introduction to Japanese life. This is the opening of Disney+’s Shōgun, and much of the drama revolves around the question of “good” means when these two very different cultures meet.

It is the year 1600 and Blackthorne is the pilot of the Dutch ship Erasmus. His ship, damaged by the storm, somehow managed to creak and move towards the coast of “The Japanese”, enveloped in a ghostly fog and with its sails destroyed.

Blackthorne, played by Cosmo Jarvis in the new Disney+ adaptation of James ClavelThe best-selling novel, Shōgun, is hardly in better condition than its ship. He is hungry, his clothes are dirty, and his hair and beard are soaked and disheveled. And things get worse when the samurai come running to shore to ask about the barbarian ship that has appeared on the high seas.

In the space of a few days, he and his crewmates are thrown into a pit and have their entrails poured out; Blackthorne is urinated on, one of the others is boiled alive, and a samurai abruptly decapitates a villager, for no reason that Blackthorne can discern. He wants to escape this horrible place and return to Queen Elizabeth’s England: to Christianity and the rule of law.

The inspiration for Blackthorne was a real-life English navigator, William Adams, whose Dutch trading ship anchored off Japan in 1600. At the time, Japan was coming to the end of long and bloody decades of civil war, during which the lords Samurai planned and fought for territory and power. The ultimate prize was the reunification of the country under the control of a single person: this was briefly achieved by the warlord Hideyoshi, but his death in 1598 plunged the country into uncertainty once again.

Adding to the intrigue were Jesuit missionaries and Portuguese merchants, who had arrived in Japan half a century earlier and had begun to obtain converts and considerable sums of money (the latter largely thanks to the control of an extraordinarily profitable trade between China and Japan. ). Raw silk sometimes retails in Japan for around ten times its purchase price in China.

No wonder, then, that the Portuguese attempted to persuade the Japanese that this Protestant interloper, William Adams, was a pirate and should be treated accordingly. Frederik Cryns, a professor of Japanese history at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto (who worked as a historical advisor on Shōgun and is the author of a soon-to-be published biography of Adams) tells me that the Englishman “was very afraid of being executed…perhaps on a cross.” Crucifixion was one of several methods of capital punishment at the time in Japan.

Adams was pardoned by warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was busy maneuvering to become the future ruler of Japan. Adams petitioned Ieyasu to be allowed to return home, but Ieyasu would have none of it. “Ieyasu really liked him,” says Cryns, “because of his knowledge as a navigator. Ieyasu probably didn’t know that England and Holland existed… so he got a whole new view of the world through Adams.”

Adams and his European crewmates built two ships for Ieyasu, after a final battle in the fall of 1600 paved the way for Ieyasu to become shogun: an ancient role whose full title in Japanese approximates “overwhelming generalissimo of barbarians.” . Adams also served Ieyasu as a negotiator with several European trading powers and was granted the high samurai rank of hatamoto as a reward, a rare honor, especially for a foreigner. Europeans who visited Japan in the 1610s regarded Adams, Cryns says, “no longer as an Englishman, but as a Japanese.” In Disney’s Shōgun, Blackthorne is taken from the coast to Osaka Castle, where he meets Lord Toranaga, based on Tokugawa Ieyasu and brought to life by Hiroyuki Sanada (The Last Samurai) as a master strategist with great gravitas.

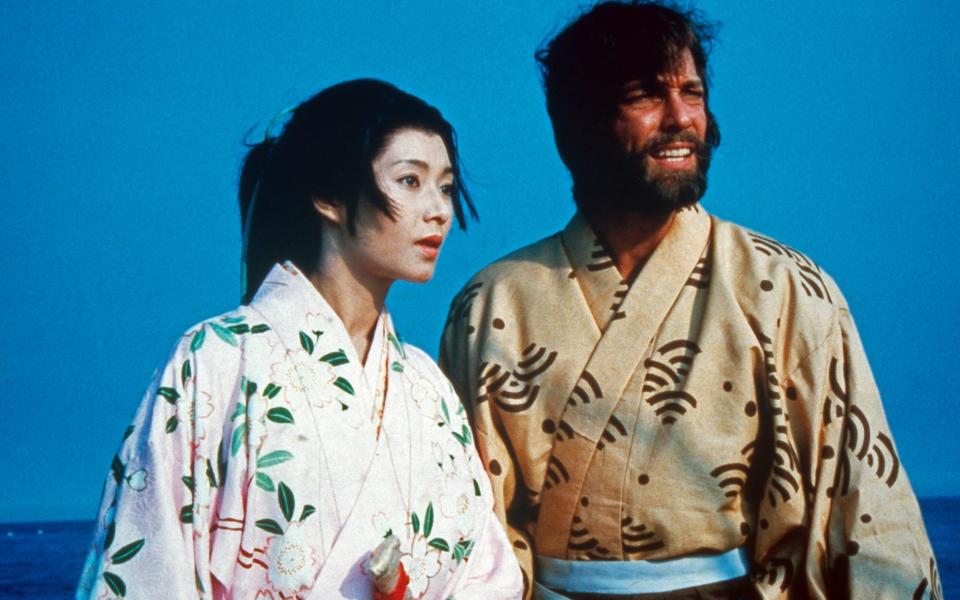

Osaka Castle and its surroundings are recreated here in lavish, painstaking detail: evidence of both a big budget and a determination to bring some balance to a story that has been told before (in Clavell’s 1975 novel and the Paramount miniseries from 1980, starring Richard Chamberlain and Toshir&omacr). Mifune – mainly from Blackthorne’s point of view. In this new adaptation, Cryns says, the American and Japanese production teams “wanted to have the point of view of all the (main) actors.” And he adds: “It is not about Westerners discovering an exotic culture. They are two cultures that come together.”

However, they do not meet for polite conversation. They were violent times in Japan. The horrible fate that one of Blackthorne’s crewmates suffered early on (boiled alive in a huge cauldron) was, Cryns says, rare in Japan, but not unheard of. The warlord Hideyoshi once punished an outlaw, Goemon Ishikawa, by having both he and his son boiled alive in public.

Shōgun also presents seppuku: ritual suicide, practiced by samurai in this era for various reasons, including dishonoring the lord. Sometimes a man’s heir may be forced to die with him, even if he is still a child. For example, Lord Blackthorne’s love interest in the new series, Lady Mariko, a Japanese Christian noblewoman, comforts a mother who is about to lose her baby in this horrible way.

One of the challenges for Shōgun is how to manage the romance that develops between Blackthorne and Mariko, who is married to a jealous and threatening warrior played by Shinnosuke Abe. When the novel was first published, Clavell was criticized for depicting Mariko jumping into a bathtub with Blackthorne. He wanted to suggest to Western readers that the Japanese are not obsessed with sex and sin. But the idea that a married noblewoman, who was also a devout Christian, would agree to share bathwater with a Western barbarian seemed ridiculous to critics, and also unfortunate, given that Westerners’ impressions of Japanese women were already They relied too much on clichéd notions of geisha and courtesans.

“Of course,” Cryns tells me, “in real life (this relationship) didn’t happen, but it could be possible.” If it had happened, in Japan of this period, Mariko’s husband “would be allowed to kill her,” along with Blackthorne. Keen to avoid spoilers, Cryns says little about how things develop between Blackthorne and Lady Mariko in this new adaptation. But he was deeply impressed, he says, by the commitment of the writing and production teams – led by Rachel Kondo and Justin Marks in the United States and Hiroyuki Sanada in Japan – to make Shōgun as faithful as possible to the historical context of he.

If samurai had been little more than murderers, it would be difficult to imagine Westerners taking as much interest in them as they have from the late 19th century to the present day. In fact, having replaced the ancient Japanese aristocracy as the country’s cultural elite, the samurai engaged in all manner of activities besides cutting, crucifying, boiling, and beheading. They read Buddhist sutras, practiced calligraphy, painted, collected art, and enjoyed performances of the notoriously subtle and allusive Nō theater. Cryns is pleased that Shōgun features both Nō and the Japanese tradition of linked verse poetry, known as renga.

In short, Blackthorne, Toranaga and Mariko are three very different characters who, however, share a powerful curiosity and an openness to new ideas. In our sometimes narrow and fearful times, these seem like completely “good” values to rediscover, whether abroad, in Japan, or at home.

Shōgun is available in the UK on Disney+ from February 27. Serving the Shogun: The True Story of William Adams by Frederik Cryns (Reaktion Books) is published May 1.

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 3 months with unlimited access to our award-winning website, exclusive app, money-saving offers and more.